Football has reached the point of no return, with clubs spending more and more each year on the biggest names around. In the first instalment of a three-part series on the flourishing transfer market, theScore explains how and why it’s become a multi-billion-pound industry.

Complete series:

- Why do agents have so much power? (Aug. 1)

- How to fix the inflated transfer system (Aug. 2)

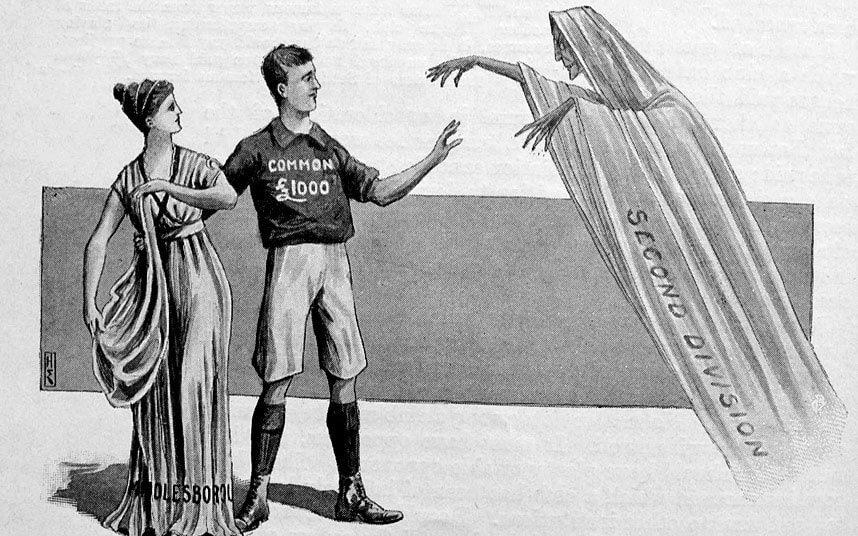

When moustachioed striker Alf Common joined Middlesbrough from Sunderland in 1905 for a then-record £1,000 fee, the world was a different place. Capitalism had just taken hold of English industry, television was a distant reality, and footballers had second and third jobs.

The transfer sparked “heated debate” in the House of Commons, according to the book, “When Saturday Comes.” How could a footballer cost so much? And why would Boro, only six years old at the time, spend that kind of money?

The answer was survival. Risking the drop, the Smoggies looked to Common to keep the club in the first division. And he did, scoring a penalty on his debut to secure Boro’s first away win in nearly two years.

(Photo courtesy: The Telegraph)

More than a century later, Common is nothing more than a laughable footnote in the annals of football’s lavish culture of spending. Transfers totalling billions of pounds happen every summer, and the costs continue to soar.

The market, once dictated by local businessmen, exploded once the game went global. As television companies one-upped each other for the chance to show top-tier matches, clubs gained a considerable amount of disposable income. Sponsorships increased revenue, and foreign owners entered the fray with their own fortunes.

The result? An overinflated transfer system in which clubs try to buy success.

And sometimes, it’s the desperation of Middlesbrough’s kind that forces the hand.

The big bang

Clubs’ coffers began to overflow in the 1990s, when TV networks realised they could sell live football as a way to boost subscriptions.

“This made the market more competitive,” Alex Duff, co-author of “Football’s Secret Trade: How the Player Transfer Market was Infiltrated,” told theScore. “Before that, in the UK, there was only one match a week. Maybe not even that, just a highlights show.”

In the early 1980s, TV rights went for around £200,000, according to Duff. Before that, clubs even paid sponsors to wear their merchandise.

Contrast that to the Premier League’s current £8.3-billion TV deal – and sponsorships in the hundreds of millions – and it’s no secret why England’s elite can and will drop bigger chunks of change for coveted players.

That difference in trends dates back to Silvio Berlusconi’s push for pay-per-view in the 1980s. By televising AC Milan’s high-profile friendlies on his network, Mediaset, he created a supply for the demand. Berlusconi also helped give life to the Champions League by encouraging UEFA to expand European competition so networks could televise as many marquee matches as possible.

Oddly enough, there’s now almost a surplus of live football on television. A top team can expect to play 50 fixtures per season – all for a sweet piece of the pie.

Elsewhere, Real Madrid and Barcelona benefited for years from generous bank loans and a disproportionate share of La Liga’s TV money, which funded the famous Galacticos in the early 2000s and the signings of Kaka and Cristiano Ronaldo. Even with new regulations in place to curb their financial monopoly, Madrid and Barcelona have enough revenue to handle hundreds of millions of pounds of debt.

And Paris Saint-Germain has emerged as a serious player on the transfer market thanks to Qatari-backed investments. Should PSG sign Neymar, the entire package, including fees and wages, could reportedly exceed the £300-million mark.

Because of the massive disproportion of money in European football, and the relative weakness of Financial Fair Play regulations, the business of buying and selling players is a high-end pursuit.

Only 10 percent of the 13,500 players who switched clubs in 2014 cost a fee, according to Duff.

The fans want more

But the Premier League has far exceeded its peers. By moving from terrestrial to satellite TV, it turned the upper echelon of the English game into one of the richest sports landscapes in the world.

As a result of the newly negotiated TV deals, the Guardian’s David Conn said the league’s 20 clubs earned a record £3.649 billion in income in 2015-16. Wages represent 61 percent of that total, which is considered sustainable. As long as the cash is coming in, there’s a will to spend.

The biggest difference between the Premier League and its rivals is the circulation of wealth. Even relegated Sunderland, which went a dismal seven straight league matches without scoring a goal, received payments just short of £100 million last season. Only the Black Cats’ level of debt restricted significant activity on the transfer market, proving that mismanagement is still a real problem for smaller clubs.

For England’s leading pack, however, there’s a higher threshold and expectation for big signings.

Faced with shortcomings in goal and defence, Manchester City has splurged nearly £300 million since the 2014-15 season to find a fix. It may now have a stable backline with the pricey acquisitions of Benjamin Mendy and Kyle Walker, but that doesn’t guarantee success.

What it does achieve is supporter satisfaction.

“The big-money signing is a way to materially demonstrate a commitment to the fans,” Stefan Szymanski, professor of sport management at the University of Michigan and co-author of “Soccernomics,” told theScore. “Building a new stand, enhancing the training facilities – while they might actually contribute to a club’s long-term success, they don’t seem as tangible to the fans. Bringing these gift-wrapped players to the fans is part of the whole relationship with the owners and elected presidents.”

The foreign invasion

Now that foreign owners have taken over the sport – which they see as an opportunity to strengthen their international profiles – the rapport between supporters and those owners is more important than ever. And spending has strengthened that bond.

The only reason supporters of Manchester City, Leicester City, and Chelsea have accepted their new lords is down to their clubs’ respective transformations. Each of those outfits left behind mid-table mediocrity or life in the lower rungs of football once billionaire foreigners spent their cash and erased debt.

Chelsea’s ever-present Roman Abramovich can hire and fire managers at a whim without losing supporters’ faith because he’s delivered top players and major trophies. Even a less visible owner like Manchester City’s Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan has had a great effect on the local community, attracting some of the world’s flashiest footballers and one Pep Guardiola.

Spending increasing amounts on newer, shinier things, year after year, has become a means by which to sell season tickets and keep the fans’ trust.

“Buying a big name is a way of saying, ‘Yes, we are a big club.’ It gives supporters the thrill of expectation, a sense that their club is going somewhere, which may be as much fun as actually winning things,” Szmynaski wrote, along with Dutch journalist Simon Kuper, in “Soccernomics.”

The gold rush

While the globalisation of the Premier League, which boasts players from 65 different countries, has certainly boosted its value, it’s also forced traditionally local clubs like Everton to find wealthy investors in search of life among the elite.

By ceding half of his 26 percent share to Monaco-based accountant Farhad Moshiri, longtime Everton board member and Merseyside native Bill Kenwright put the club in the hands of someone who could finance it like cross-town rival Liverpool.

Stabilising finances, as Kenwright did during David Moyes’ frugal tenure, was no longer a concern.

Everton didn’t need to sell Romelu Lukaku to Manchester United to spend around £100 million. Instead, Moshiri’s investments gave the Merseyside outfit the ammunition to recruit Davy Klaassen, Michael Keane, Jordan Pickford, Sandro Ramirez, and Wayne Rooney.

There’s now talk the Toffees could crack the top four.

“You can never take over a club. You become part of it and that’s what I’m hoping – to become part of a club,” Moshiri said in March 2016, after purchasing a 49.9 percent share. “For me, I bought into a new family and that’s what is special for me.

“I give them whatever I have.”

(Photos courtesy: Action Images)