A new cycle has begun at Manchester City.

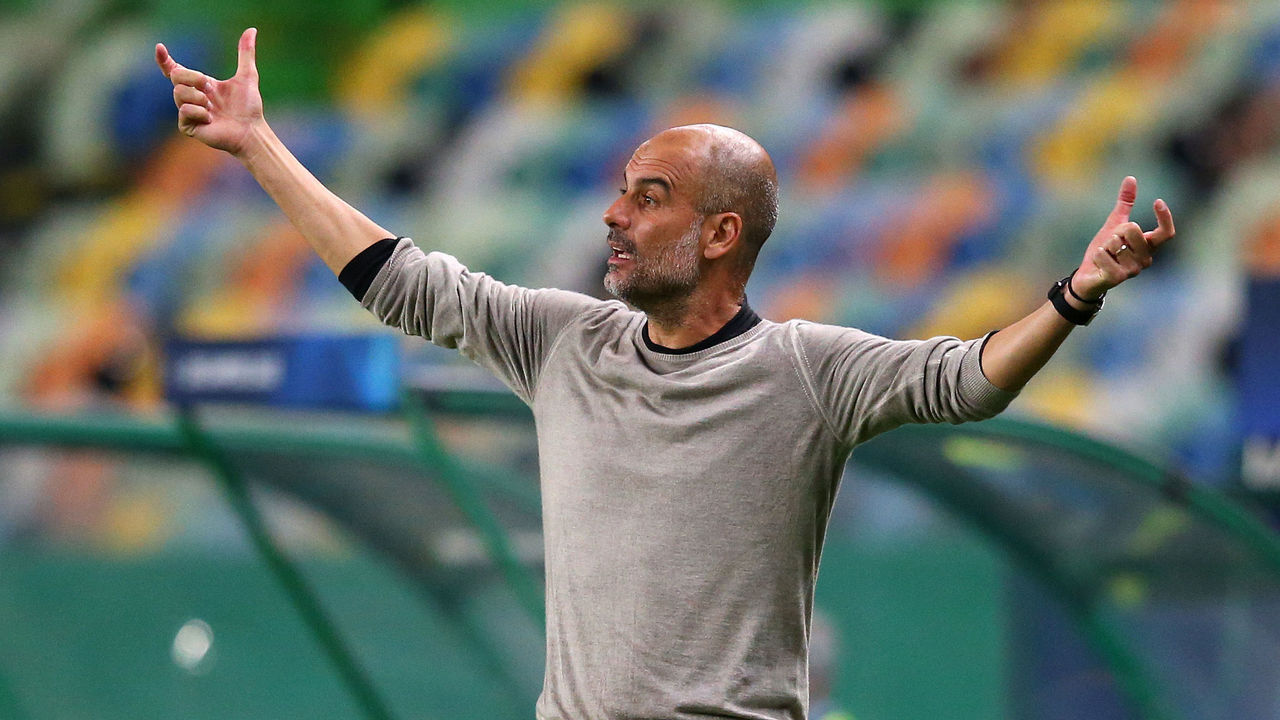

Pep Guardiola has entered uncharted territory, already spending longer in east Manchester than he did in the technical areas of Barcelona and Bayern Munich. Last season, his side surrendered its two-year grip on the Premier League trophy to a dominant Liverpool. The spine that predated Guardiola’s reign is distorting and disintegrating: David Silva left one year after Vincent Kompany’s departure, and Sergio Aguero and Fernandinho could follow in June.

The squad that he fine-tuned needed an upgrade after August’s Champions League elimination to Lyon. The conservative setup in that hugely disappointing defeat – to France’s seventh-best club, at the time – was strangely familiar.

Raheem Sterling missing an open goal from five yards was 2020’s version of Lionel Messi reading Jerome Boateng a bedtime story before tucking him in for the night. Guardiola was his own worst enemy against Lyon, just as he was in Bayern Munich’s infamous 3-0 semifinal first-leg defeat to Barcelona in 2015; Sterling’s gaffe and Boateng’s tumble were tragicomic byproducts of a manager sapping his teams’ trademark vim and verve at a crucial moment.

“The gaps were little, but you have to close these gaps. We have to solve it,” Guardiola said in October after claiming responsibility for the Lyon defeat.

“It’s the past. Now is a new opportunity, and we are going to start at zero again.”

The Lyon loss ended a Guardiola cycle at City. But, unlike his spells in Spain and Germany, the 49-year-old appears to be sticking around for another.

The innovator

His early days at City presented, until this season, the toughest assignment of his managerial career.

At Barcelona, the departures of Ronaldinho and Deco offered the biggest hint of what would follow, as Guardiola increased the club’s reliance on the gifted academy products rising from La Masia. Bayern didn’t require a revolution either, so upon his arrival, he merely insisted the board sign Thiago Alcantara to complement the riches he inherited: the waspish wing play of Arjen Robben and Franck Ribery, the versatility and defensive protection of Philipp Lahm and Bastian Schweinsteiger, and the tactical genius of Thomas Muller.

The City project was more daunting. Despite the previous summer’s acquisitions of Sterling and Kevin De Bruyne, sterility had set in during Manuel Pellegrini’s time in charge. The full-backs were rusty and the hapless Eliaquim Mangala was a regular at center-back. Yaya Toure idled his way through matches. Kelechi Iheanacho and Wilfried Bony, the two strikers vying for minutes behind Sergio Aguero, scored 12 league goals between them in the 2015-16 term.

Pellegrini’s side finished a considerable 15 points adrift of title-winning Leicester City and only squeezed into the top four on goal difference. City had collected two Premier League titles in six seasons; hoisting silverware was yet to become a habit. Guardiola had work to do if he was to preserve his reputation as a cup hoarder.

Yes, he spent money, and he wasted plenty of it on defenders. But it was the nature of the success – the tactical innovations and downright dominance – that set City apart. The players recalibrated the English game when they fully grasped Guardiola’s methods in Years 2 and 3.

“He’s been an innovator. When I watch kids’ football now, when they can get on pitches that aren’t flooded or frozen, I see them playing out from the back,” said England manager Gareth Southgate in 2018.

Southgate would know. Burnley’s Nick Pope is probably the best shot-stopper available to England’s national team, but error-prone Everton goalkeeper Jordan Pickford keeps hold of the No. 1 jersey due to his footwork and distribution. The sight of a full-back wandering into a central position isn’t that kooky anymore. Teams in the fourth tier and below are splitting their center-backs and dropping in a central midfielder to instigate passing moves from the base of the lineup. Each development is influenced by what Guardiola brought to City following his 2016 unveiling.

‘Different year, same stuff’

A Guardiola regime comes at a cost. The mental wear on the Barcelona and Bayern squads was obvious when Guardiola neared the end of those respective spells, and four years of him vibrating on the Etihad Stadium touchline appeared to reach its inevitable, messy conclusion in August. The exhaustive tactical tutoring and team talks had seemingly taken their toll.

“Different year, same stuff,” De Bruyne shrugged after the Lyon match. The Belgian was recalling his previous Champions League disappointments with the club, against Real Madrid (under Pellegrini), AS Monaco, Liverpool, and Tottenham Hotspur.

Sometimes, accusing Guardiola of overthinking tactics is a ready-meal offering by journalists without the time or inclination to cook up anything better. However, while Guardiola’s unrestrained approach against Monaco was naive, over-scrutinizing rivals to the extent that it blunts his own side’s strengths was a fair hypothesis for both the Liverpool and Spurs exits. He was also questioned for the tactics that accompanied Barcelona’s elimination in 2012 and Bayern Munich’s inability to reach a final in each of his three seasons in Bavaria, which included the Boateng game.

Guardiola has furnished an unwanted reputation at City.

“In knockout games, Pep pays a lot of attention to the opponents and their strengths,” Muller, who collected seven winners’ medals during Guardiola’s Bayern spell, explained to The Athletic in February. “He’s always a little torn between paying extreme attention and respect to the strengths of the opposition – more so than against smaller teams – and sticking to his convictions and to a system he believes in, to go, ‘We will play with that risk because that’s who we are.’

“Sometimes, it’s not 100 percent clear what we’re doing.”

City were drained when they trudged off the pitch in Lisbon. On home soil, a League Cup final win over Aston Villa would never compensate for the 18-point gap below Liverpool in the Premier League table.

Renewal

Nowadays, most elite clubs hire managers with hopes of sparking success through a three-year period before the squad, training-ground routines, and on-pitch setup need refreshing with new leadership. Guardiola is in his fifth season at City and repeatedly states he wants to remain. “It is a place I love to be, but I have to deserve it,” he declared in September.

Something is keeping Guardiola at City. It might be a desire to prove people wrong. It certainly helps Guardiola to have ex-Barcelona teammate Txiki Begiristain and Ferran Soriano, a former executive at the Catalonian club, in the boardroom to continually back his plans, but there is evidence of renewal to counter any suggestion that Guardiola is losing his hunger for the job or getting too comfortable.

The recent disjointed performances bear resemblances of Guardiola’s first season, with players working out each other and the tactics all over again. The repeated injury absences in the squad have forced the Spaniard’s hand, of course, but he does seem to be steering his side into a new phase.

Bernardo Silva is deployed in wide areas less frequently since David Silva ended his decade in sky blue, with the former’s all-action performance against Arsenal in mid-October perhaps a sign of what’s to come. Phil Foden’s influence on the team is increasing, and he’s developing a promising understanding with summer arrival Ferran Torres. After plenty of trial and even more error, the heir to Kompany’s defensive mantle may be Ruben Dias.

And, most pleasingly for the club’s supporters, academy kids are earning first-team minutes with greater regularity – nearly six years after City moved into the £200-million Etihad Campus. Six of City’s 12 substitutes for the Champions League group-stage wins over FC Porto and Marseille were players who’ve passed through the club’s youth ranks.

Guardiola could’ve taken the easy way out. He wouldn’t need to look far for new employers, and Juventus had a vacancy in the summer, but he’s trying to revise one of his own creations for the first time in his career.

It could rewrite his managerial legacy. Re-enlivening a team that appeared to fade under his watch would hush criticism that players grow fatigued of his demanding nature, and guiding City to Champions League success would turn the volume down on the overthinking jibes.

Failure, on the other hand, would mean the critics have won.