Rebuilding Arsenal: Time to excavate the Wenger regime and start anew

How Arsene Wenger has transformed Arsenal since his 1996 arrival is remarkable. The lager was whittled out of the players’ diets at a club that bore a reputation of playing boring football, and in its place rose a supremely fit side showcasing some of the most beautiful patterned passing English football had seen. It was often played by leggy imports that changed the landscape of the country’s game.

The narrative has staled since “the Invincibles” romped to the Premier League title in 2003-04 though. Each season has bored into a more repetitive and sorry sequel, until Wednesday’s 5-1 humiliation at Bayern Munich showed a gulf in class that simply cannot be bridged under the watch of Wenger. Chelsea had done something similar earlier in February.

It’s been stasis at the Emirates Stadium for over a decade, and the supporters that want a divorce from Wenger reach far beyond the monosyllabic grunts and barks of Arsenal Fan TV. Plenty of blame for this inactivity will also be fairly apportioned to the boardroom; a hierarchy that has put ensuring the club is a marketable entity over making it a trophy-winning force.

The crowded French market

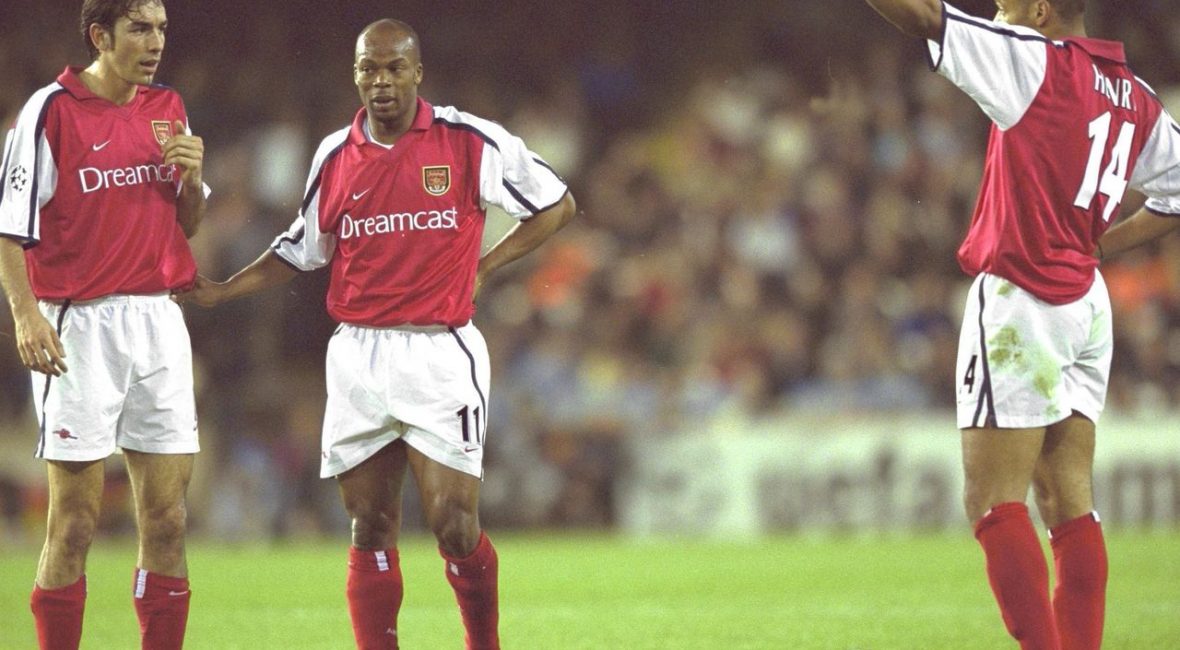

Wenger was a pioneer at the beginning, but perhaps it was partly because his outreach was unmatched. Patrick Vieira, Nicolas Anelka, and Emmanuel Petit soon joined his Highbury revolution as the long-coated tactician plucked players from France, his native land and where he guided AS Monaco to the 1987-88 Ligue 1 title.

Others followed in the ensuing years, like Juventus flop Thierry Henry, Sylvain Wiltord, and the wing musketeer Robert Pires, but it has since dried up. Laurent Koscielny and Olivier Giroud pose the only successful arrivals hailing from that region in the last nine seasons. Maybe the important numbers in Wenger’s address book lost influence or contact, or maybe it’s just the Gallic market is now saturated with scouts. Newcastle United’s chief talent spotter Graham Carr has ravaged it in the past, and Steve Walsh plucked N’Golo Kante and Riyad Mahrez from there for Leicester City – the kind of players that would’ve likely fallen onto the lap of Wenger 15 or so years ago.

Like with the diets and training methods at Arsenal, the scouting is vastly improved across the Premier League. The old flat-capped blokes who scribbled notes on the back of cigarette packets are figures of a bygone era; players are analysed on a laptop by studious people with sensible haircuts. Manchester City, a team that used to pick up aged rejects from the likes of Arsenal and Liverpool, now has its fingers in North America, Asia, Australasia.

Top four and no more

There’s another point of contention that rang the death knells long before the recent withering and wimpering of Wenger’s regime: Arsenal, a sports behemoth with a 60,000-capacity ground and merchandise worn in all corners of the globe, refuses to flex its muscles in the same manner as its compatriots and other sides that habitually compete in the late rounds of the Champions League.

True, setting up something akin to the City Football Group may be a stretch – there are deep resources at Manchester City’s Etihad Campus – but the cosy relationship between the elusive owner Stan Kroenke and Wenger has anchored the club in comfortable routine. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Kroenke, a shrewd businessman who’s involved with well-run yet not particularly successful sports franchises, and a qualified economist in Wenger are overseeing an operation run purely for a handsome bottom line rather than silverware.

There’s no doubting Wenger wants to win trophies, but the need to remain in the black is paramount. Mesut Ozil and Alexis Sanchez were acquired for vast sums, but under immense pressure from the support – it was the same situation with the late summer signings of Shkodran Mustafi and Lucas Perez this season – while other dearths in the squad (the need to sign a top quality striker or, most importantly, for a defensive midfielder of bite and intelligence) haven’t been addressed. The club is rich, so this lack of investment is merely a miserly practice that denotes a distinct lack of ambition.

Kroenke isn’t guilty for the other aspect, though. Wenger hasn’t adapted to the new frantic world of reactive tactics, and continually plays favourites in his team selections.

Time to go

At Bayern Munich, there were no new ideas. There was no game plan deployed to stymie a better team. Paris Saint-Germain’s tactical clinic in besting Barcelona by a 4-0 scoreline a day earlier was encouraging for the Gunners’ support, but they were instead given the same drivel.

Arsenal’s players don’t look drilled in a system, or disciplined in the slightest. Ozil, someone who should’ve been under consideration for the axe in a fresh approach, was listless and resembled a skulking child, and Francis Coquelin and Gabriel Paulista again showed that they are not good enough for a side with title aspirations. Yet they hang around, and the Emirates Stadium coffers remain full.

Wenger has to go, but with all he did for the club in the first half of his stay in north London it has to end amicably. Let him know his tenure is reaching its end, and include him in the recruitment process for the next manager.

Sir Alex Ferguson’s recommendation of David Moyes didn’t work particularly well at Manchester United, but the wily Scot had left his successor with an aging squad. There is no such caveat at Arsenal, and it could take a while for the new boss’ ideas to take hold, but a change needs to happen so the club isn’t left behind. And for the sanity of its support.