The road signs dictated you could only turn right out of Barnet’s training ground, but Edgar Davids would point his car down the bus lane. He incurred fines for turning left each day but, for him, traffic restrictions in north London were merely suggestions. It was the quickest way home.

Barnet’s director of football at the time, Paul Fairclough, knew such behavior was typical of Davids. “He’s his own person. No one’s going to tell him what to do.”

Davids launched his managerial career in October 2012 with an aim to improve technical play throughout English football. The fact that he was player-manager of fourth-tier Barnet – a club that had spent 107 years of its 124-year existence outside the country’s professional leagues – was just another roadblock he could ignore. He was confident he’d make an impression.

The Dutchman appeared to call time on his decorated playing career two years earlier at Crystal Palace but had since developed a reputation for cropping up in amateur five-a-side games across London. Davids’ continued appetite for the game was indisputable, and his experience from 74 international caps and hoarding of medals across European football was an obvious asset.

Barnet chairman Tony Kleanthous sensed an opportunity. His team avoided relegation into non-league football on the final day of each of the previous three seasons but, with three points from the opening 11 matches of the 2012-13 League Two campaign, performing a fourth escape act was going to be difficult. He needed a spark from somewhere.

Davids had recently participated in a charity match in the capital, so Kleanthous asked its organizers if they could put him in touch.

“I met him at a hotel in town,” Kleanthous told theScore. “We immediately struck up a rapport and I just offered him the opportunity there and then.”

Davids had no coaching experience, but his football philosophy that began to form in Ajax’s famed youth academy gave Kleanthous confidence that he was the man to turn Barnet’s fortunes around.

Kleanthous and other key members behind the scenes insist there were no commercial motivations behind hiring Davids. There was too much at stake: Barnet were set to move into a modern stadium the following season – effectively signaling a new era for the club – and relegation would cause a financial shortfall nearing £1.5 million. There were no parachute payments to soften the blow for demoted sides. Davids needed to ensure Barnet stayed in the English Football League (EFL).

Davids, of course, backed himself to handle such a daunting task and much more. “I am trying to help English football be more diverse,” he ambitiously declared while slamming the national team’s style of play a day after his appointment.

To assist his revolution, the 39-year-old would play as well.

The disciplinarian

Ulrich Landvreugd first met Davids while playing football in the squares of Amsterdam. They were aged 12 or 13, and Landvreugd was immediately struck by Davids’ “temper and his will to learn and do tricks.”

Ajax spotted the players’ promise, and the pair went on to play in the storied club’s Under-18 and reserve teams together. However, Landvreugd’s succession of injuries crushed his dream of playing alongside his friend for the senior side. Their bond remained strong, and Davids quickly enlisted Landvreugd – who was then coaching Blauw-Wit Amsterdam – as his assistant at Barnet.

Landvreugd had already identified elements of Davids’ personality that would translate well into coaching. There was no questioning his passion, but Landvreugd witnessed something else during a trip to visit Davids when he was playing for Tottenham Hotspur.

“When everybody was finishing with training, he went to the Under-18s, helping the guys to do tricks or one-against-one,” Landvreugd recalled. “That’s Edgar, he still wants to help young kids to get better.”

Davids, it turned out, was a disciplinarian. He told the Barnet players to call him “sir.” His mentality was of someone who had won the Champions League, UEFA Cup, and a surfeit of domestic honors in the Netherlands and Italy, rather than a mentality usually associated with the bottom end of English football. And as player-manager, he could set those standards on the practice pitches.

“I always used to see him smash players,” Mauro Vilhete, who was a young winger on Barnet’s books, said of Davids’ intense training sessions.

“There were times where I’d just get in front of him or nick a ball and just go past him and you could just hear him coming, coming from the back. He’s just chasing you down. Yeah, he left one or two on me.”

Landvreugd and Fairclough both credit Davids for quickly identifying strengths and weaknesses in players. More than anything, it was his uncompromising approach to training that helped him weed out those who seemed to lack the fight or ability required to be in his team.

“He was demanding in training, to be honest. Very demanding,” Andy Yiadom, who now represents Reading and Ghana, shared. “I remember there were times – I’m not going to mention any names – he made people cry because of how demanding he was.”

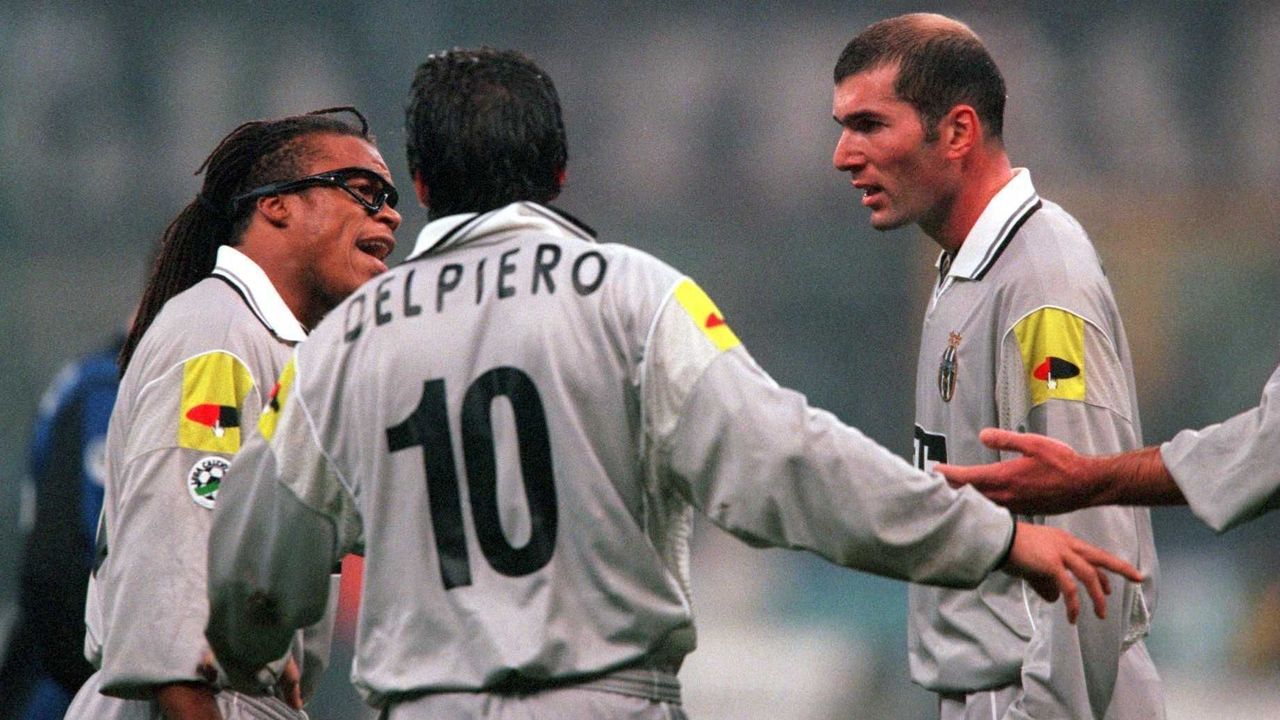

Davids would vent his frustration if players couldn’t perform to his level. It was a level of someone who had worked with icons like Zinedine Zidane, Xavi, Paolo Maldini, Ruud Gullit, and Ronaldinho. It was a level that Vilhete, Yiadom, and their teammates had to try to meet each day.

“The majority of them, yeah, go into the shower and stuff and they wouldn’t play no more,” Vilhete said of the players who angered Davids. “But when you stuck up for yourself and you put yourself about, you gained his respect.”

Davids’ debut in the dugout was sullied by a 4-1 home defeat to Plymouth Argyle, which left the team a considerable seven points adrift in the relegation zone after only 12 matches. Optimism was in short supply. Only 2,721 fans were drawn to the next match when Davids was fit enough to make his first professional appearance in almost two years in a visit from Northampton Town.

It was worth the price of admission.

“It was as if the clock had been turned back 15 or 20 years,” Fairclough marveled. “We were all exhausted by the end of the evening with his passion and his enthusiasm and his desire to win the game.”

Barnet won 4-0. The Davids era had begun.

51 points

Except that it wasn’t strictly the Davids era – the Dutchman had entered an arranged marriage. Mark Robson, who had overseen Barnet’s wretched start to the season with a vastly inexperienced squad, was still in charge in a co-manager capacity.

Fairclough says it was clear that neither party was happy with the arrangement at their first meeting. Within weeks, they were actively avoiding one another. And it was soon apparent that Davids would make his own mark on Barnet, regardless of Robson’s presence.

“Edgar is a person who doesn’t compromise,” chairman Kleanthous said. “He has his beliefs and he will stick to those steadfastly, and that causes a problem if you’ve got two people in charge. He’s a person who needs to be in charge of his own thing. It’s something I should’ve recognized sooner.”

Barnet’s form improved significantly when Davids and Robson co-managed, rising from 0.27 points per game to 1.46. That rate, if collected from the start of the campaign, would’ve been enough to challenge for seventh place and therefore a shot at promotion via the playoffs. But Davids’ ego and stubbornness weren’t conducive to a coaching partnership. The arrangement wore Robson down.

“It came to the point where Mark had sort of been, I suppose, beaten up emotionally,” Fairclough explained. “It was better for his well-being and his mental health that he went.”

When Robson departed in December 2012, Davids could decide how to meet his objectives on his own. Kleanthous soon set him a target of 51 points for survival in League Two. “No club’s ever been relegated with that number of points,” the chairman remembers telling Davids.

Landvreugd said they attempted to introduce possession-based football while appreciating that sometimes the team had to go direct. However, when Davids was on the pitch the game plan could appear simple: Pass it to the boss.

“I felt, personally, that I had to cater for him,” admitted Yiadom, who still admires Davids and felt his game improved under the Dutchman’s watch. “I just remember being more comfortable with him being a manager on the sideline.”

Davids demanding the ball was a regular soundtrack to Barnet’s matches. “Some players, if you want to keep your place, you give it to him because if you didn’t at halftime he’s in there screaming at you, ‘Give me the ball, give me the ball, give me the ball’ and blah, blah, blah,” Vilhete said.

The veteran midfielder’s personal struggles with losing could interfere with his management. Vilhete recalls a halftime break at Accrington Stanley when Davids’ fury with the 3-1 deficit kept him from addressing his players. “It was bizarre. I’ve never seen nothing like that before.”

Barnet’s results leveled out a little following Robson’s departure, but an average of 1.3 points per game still outdid their rivals at the bottom of the table. The Bees were only one win away from their target of 51 points ahead of their penultimate match of the season; and the occasion doubled up as an emotional farewell to Underhill – the ground with an infamous sloped pitch that had served the club for 106 years.

Impossible becoming possible

The game started at least 15 minutes late to allow time for 6,000 fans to cram into the venue. Barnet were still in trouble despite closing in on their points target – as were seven other teams in a tight relegation battle.

It looked as if Barnet had procured three crucial points in the 81st minute when Jake Hyde stabbed the ball in from close range. But it wasn’t going to be that easy. Davids, who appeared omnipresent for 85 minutes before he left the game with tight hamstrings, kicked and punched the home dugout when Barnet conceded a 92nd-minute penalty.

But Graham Stack saved it, etching his name into Barnet folklore. Jubilant supporters invaded the pitch at the final whistle to embrace their heroes, and Davids was unsurprisingly at the center of it. The 1-0 win was a fitting way to close the door on Underhill and, although 51 points weren’t necessarily enough for survival, Barnet’s fate was in their own hands. They sat one point above the relegation zone with one game left. Davids had almost completed a seemingly impossible task.

The final match of the season was at Northampton Town. The hosts had already secured a playoff place, and Barnet could take confidence from beating them 4-0 in Davids’ playing debut.

So, naturally, things went wrong.

Kleanthous thinks the team may have celebrated too much after the Underhill drama and wonders if Davids made too many changes to the lineup. Landvreugd attributes the result to the brilliance of body-building frontman Adebayo Akinfenwa, who was brought off the bench for Northampton and apparently changed the game. Fairclough said Davids was “giving everything he absolutely had, but the players around him froze on the day.”

Barnet’s 2-0 defeat and AFC Wimbledon’s 2-1 win over Fleetwood Town meant the Dons and Bees swapped places. Barnet went down on goal difference and with the highest points tally ever collected by a team relegated from the fourth rung.

“He’d got these 51 points – maybe if we’d have said 53 points he’d have done that. I think Edgar left feeling that he’d done his bit,” Fairclough said of a relegation that meant redundancies for over half of the club’s staff.

“I buried a lot of this season and the season afterwards, if I’m being honest, such was the pain.”

Target on his back

Davids stayed despite Barnet’s fall into non-league and quickly made a gesture that seemed to underline his status at the club. He took the vacant No. 1 jersey – the digit traditionally worn by a team’s first-choice goalkeeper and never by an outfield player.

“I think he just wanted it to be his show, kind of thing,” Vilhete considered. “But at the end of the day, he’s Edgar Davids, he’s won it all, what can you really say?”

Whether or not it was Davids’ intention, peers and rivals deemed his choice as an unsubtle declaration that he was No. 1 at Barnet and maybe in the National League itself.

“He might as well have been on the pitch with a bullseye on his shirt because he very quickly became a target of other clubs,” Fairclough said of the No. 1 jersey. “And Edgar was responding in the only way he knew, and that was to retaliate.”

Dutch tactician Louis van Gaal nicknamed Davids “the Pitbull” at Ajax, and it stuck throughout his playing days. He barked and snarled. His tackles had bite. His aggressiveness was no secret, but non-league players proved particularly effective at bringing it to the surface.

In his eight league outings in the 2013-14 season, the 40-year-old Davids escaped only two matches without punishment. He emerged from three with a yellow card, was dismissed twice for picking up a second yellow, and received a straight red when his elbow on Stephen Wright drew blood from the Wrexham defender’s mouth.

Davids’ indiscipline put his players in an awkward position.

“We all get frustrated (with Davids). 100 percent. Every time – especially when it costs us,” Vilhete said. “It’s frustrating as hell. But what can you say, at the end of the day? He’s our boss.”

The suspensions racked up. Kleanthous questioned whether Davids had the drive to work in non-league football before he embarked on a “draining” campaign. Nevertheless, his on-pitch graft was at odds with his allegedly diminishing interest.

“When Edgar put his boots on and get on the pitch, there was no sign of the fact that he didn’t care,” Fairclough claimed. “Edgar cared about the ball and the rest of the players around him. He was cajoling and encouraging and shouting, everything that you’d expect a player-manager to do.

“Except he was absent on these away games.”

Fueled by passion

While Davids played and managed Barnet he was also running his clothing company, MONTA, a business venture which would often take him overseas. Time was a valuable commodity, and his additional duties started to conflict with his day job after the club’s drop into the fifth tier.

Landvreugd claims Davids had an agreement with Kleanthous that allowed him to skip lengthy away trips that ate into two days of his week, but the chairman disputes this. However, Kleanthous does concede there were a “couple of occasions” when Davids told him other commitments prevented him from traveling.

Fairclough was dismayed at how Davids appeared to be “picking and choosing” when he turned up to away matches, leaving Landvreugd and fellow coach Dick Schreuder in charge for matches in places like Gateshead and Hereford. Vilhete thinks the boss simply decided to miss road games and training when he was suspended. Yiadom can’t recall Davids ever offering an explanation for his no-shows.

The squad felt let down, even neglected.

“He was not swanning around, he was always busy working,” Landvreugd offered in defense of his friend.

It was the beginning of the end. There were unique aspects of Davids’ approach to management that Barnet would tolerate and even embrace, but not turning up to matches was one step too far. The club and legendary midfielder mutually agreed to part ways in January 2014, 15 months after his shock appointment as player-manager.

Incredibly, Davids refused to be compensated for his spell with Barnet, instead passing his salary onto his two assistants. His tenure was fueled by passion and little else, and it remained his only job in management until he was unveiled by Portuguese third-tier side Olhanense this January.

“At times, when you’re in this world, you sometimes question your sanity, but you look back on it and think, ‘You know what, what different and magic times they were,'” Kleanthous shared.

Kleanthous remembers when he once stood talking to Davids at the training ground when a bus pulled up at the neighboring facility for international teams. It was carrying Ronaldinho, Neymar, and the rest of the Brazil squad as they prepared for a friendly match against England in London.

A group of them headed over to have a conversation with an icon who happened to be Barnet’s player-manager.

“There I am standing there talking to Edgar Davids and half of the Brazilian national team and I’m thinking, ‘Wow,'” Kleanthous said. “When I was playing with jumpers for goalposts could I have ever dreamed of this? Come on.”

He added on the Davids regime: “Would I ever do it again? In a heartbeat.”